|

When I told the previous owners of the house that I intended to plant vegetables in the yard, they looked panic-stricken and said I shouldn’t do that because they had used a lot of pesticides. Cue lots of research on my part and a conversation with a soil scientist, and the conclusion was that pesticides weren’t as dangerous to human health as lead or arsenic in the soil. When we got the place, the soil was devoid of any life that wasn’t microscopic, so we decided to add organic matter to the soil in the form of wood chips and leaves, and then wait for life to return. And it has! I found at least a dozen worms today as I dug some paths. It’s reassuring to see them. Worms found in the winter are going to be the European nightcrawler, which came to North America with the colonists and fit in well with the local ecosystems. There is another worm, the Asian Jumping Worm, that has recently arrived and poses a threat to our ecosystems, due to its voracious eating habits. This is a jumping worm. And yes it is a picture of a photo on my phone because good lord I am going to switch away from Weebly as a website host very soon. These worms are like a sleek muscle, and the white band around their neck is even with their body, not raised. I had to look at a lot of pictures and videos to be able to determine which was a nightcrawler and which was a jumping worm, but I’ve learned to distinguish the difference easily and so can you! I had them last fall and I will keep an eye out for them in the spring (they cannot survive our winters as adults but their eggs can). Unfortunately, at this time, they should be killed when they are found; they pose a huge threat to our environment. My question, to which I haven’t found an answer, is: What do they eat in their native Japan? How can we use their natural tendencies to lessen their impact here? I will write more about them in the spring. I found this video to be very informative when I was looking for more information last fall, in case your interest is piqued: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JvxrcYbIKk Now I will go do a little celebratory dance to welcome the worms.

0 Comments

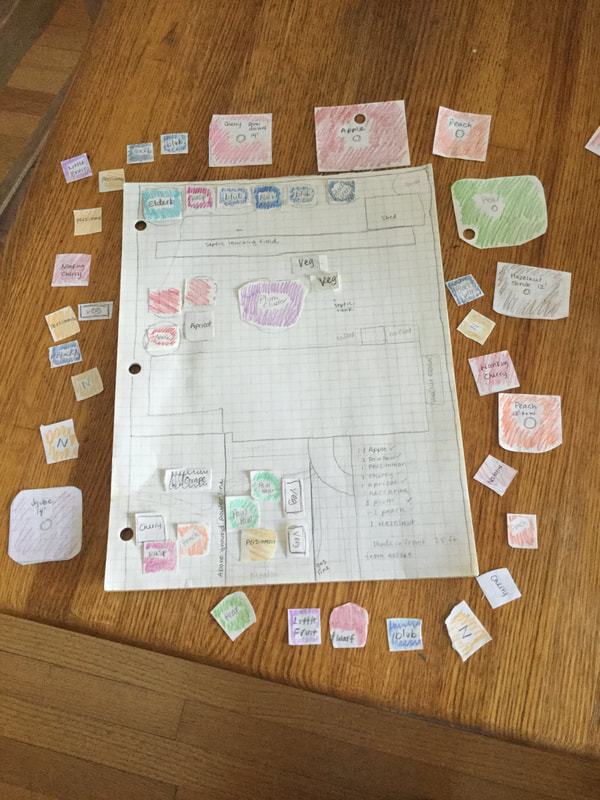

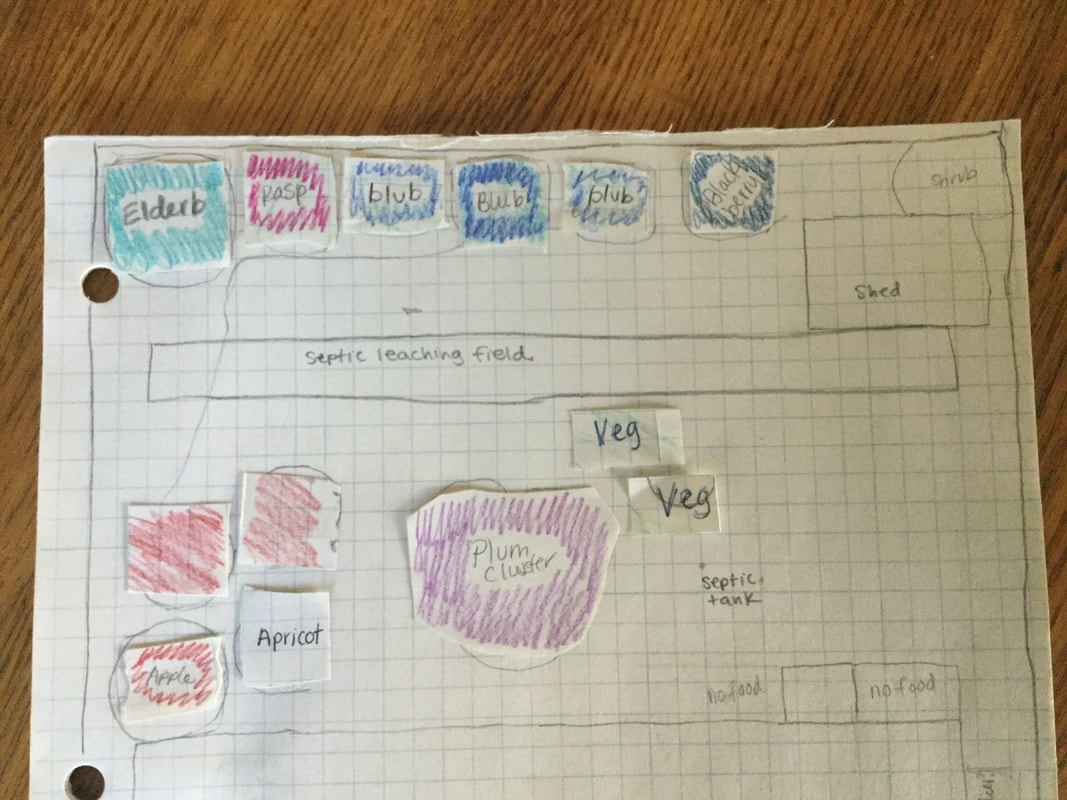

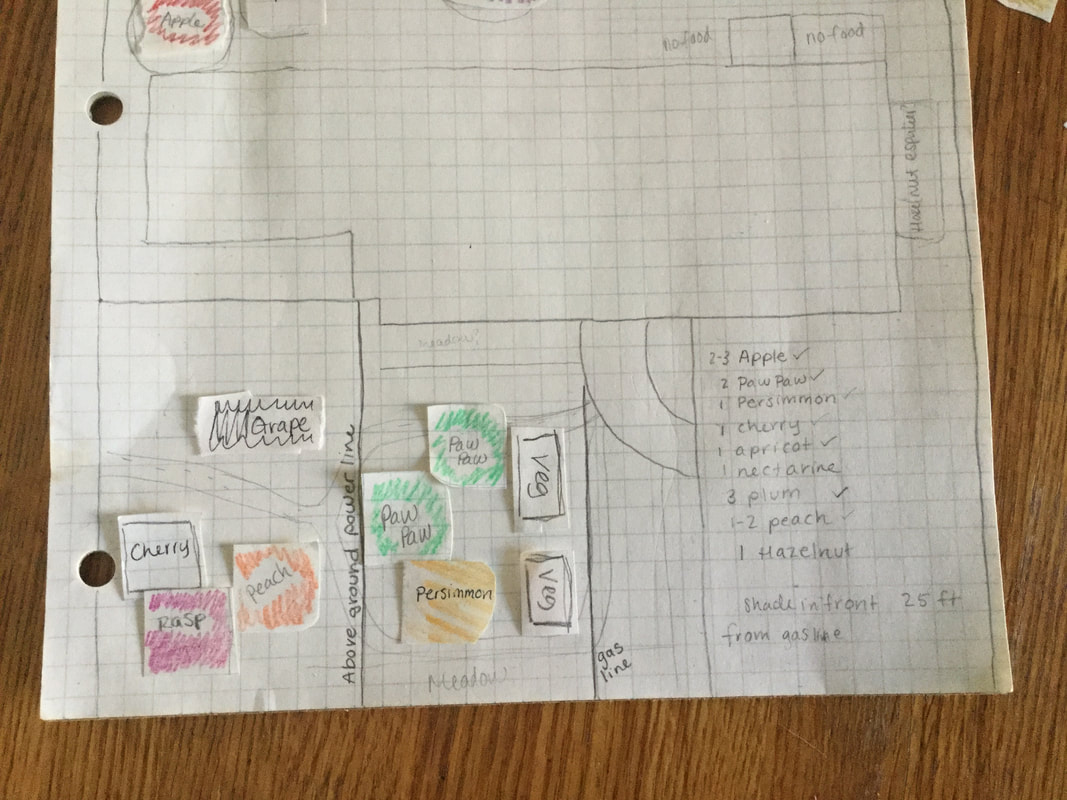

The herbaceous layer of a food forest is not just grass, though gardeners can leave the grass while they install the forest over a period of time. (Just don't allow grass within a two-foot circle of newly planted trees). The ground layer consists of carefully chosen plants that serve seven different functions, ideally with each plant serving two or more functions, for efficiency. In general gardening theory, maintenance is easier and appearances are cleaner when the garden contains fewer species planted in clumps and drifts, as opposed to a collector's garden with one of everything. The plants in a food forest help the system take care of itself without needing to add fertilizers or pesticides. Some may still be necessary for the fussier fruit trees, but they should be considerably limited. The seven functions are as follows: 1) Nitrogen fixing. Nitrogen promotes green growth, and it is the limiting factor in all forests; the system can only grow as the available Nitrogen allows. Some plants capture Nitrogen from the air and store it in their roots, diffusing it to neighboring plants. Creating a Forest Garden by Martin Crawford contains excellent resources for all of these functions. Here I will just tell you my plant choices. Lupine Lupinus perennis. This is our native blue Lupine, host to the Karner Blue butterfly, which has been driven nearly to extinction and is no longer found in CT. New Jersey Tea Ceanothus americanus. This is a native shrub, whose leaves can be used for tea, or rubbed to make a foamy soap. Bayberry Myrica pensylvanica. Another Latin name that indicates that it's native to this continent. You can use the leaves as a substitute for bay leaves. 2) Other nutrient fixers. Fruit trees need other nutrients in addition to Nitrogen, such as Phosphorus, Calcium, etc. Deep-rooted plants mine the soil for nutrients and bring it up to the surface for other plants to use. The nutrients become even more available when the leafy part of the plant is cut off and lain around the garden to decompose into the soil. I will be using: Comfrey. Chop down once or twice a year and lay around fruit trees. A powerful nutrient accumulator. Only plant it where you're certain you want it, because it can become a nuisance. Typically I'm wary of plants like this, but I've grown it before and it's so useful. Yarrow Achillea millefolium. I'm a little nervous about this one. Supposedly it's very aggressive, but it's native, so I'm a little more comfortable with that. And it serves so many functions. Watch how often it appears on this list. 3) Differing root zones. Trees have shallow roots that reside within the top two feet of soil, extending out as far as twice the width of the canopy. But there's so much space in the soil! You might as well plan to use it by planting things with differing root depths. This allows for maximum nutrient absorption and water capture which benefits the whole system. New Jersey Tea. Deep roots. Yarrow. Deep roots. Comfrey. Deep roots. Wild Strawberry Fragaria virginiana. Shallow roots. Viola. Shallow roots. This is the only food source of the Fritillary butterfly, so I'm including it in the plan. It's always good to plant for specialist species like this, to ensure their survival. 4) Ground cover. When the soil is covered by plants you want, you'll have less appearance of plants you don't want, i.e. weeds. Ground covers also retain moisture in the soil and prevent erosion. In annual vegetable gardens, mulch serves this function, but in perennial gardens it can be accomplished with plants for reduced maintenance. Wild Strawberry Fragaria virginiana. A very aggressive ground cover. Good lawn alternative. I may regret planting it if it takes over everything, but it's also a great wildlife plant. Nasturtium. This is an annual, so I'll seed it each spring, until the ground is so covered that there's no space for it. 5) Bee attractant. You want your fruit pollinated and you want to feed these lovely creatures. There are a million bee plants out there, so the main challenge will be choosing which ones to use! Garlic chives Lupine Nasturtium Viola 6) Beneficial insect attractant. These fall into a separate category from bees because they do different things. The most common ones are predatory wasps and flies, who lay their eggs in caterpillars, which in turn kills the caterpillar. Hopefully they mostly target fruit pest caterpillars and not our lovely native moths and butterflies, but you can't control it. The only thing you can do is provide lots of different native plants to attract a variety of insects and birds, and they'll balance each other out somehow. Yarrow Achillea millefolium. Anything with an umbrella-like flower consisting of clusters of tiny flowers will attract beneficial insects. Golden Alexander Zizia aurea. the original, native food of swallowtail butterflies. A somewhat traitorous plant, I suppose, as it also attracts the wasps who kill them. 7) Aromatic plants. Another layer of defense against fruit pests, these plants deter them from ripening fruit by confusing their senses. Oregano Chives Lemon balm Yarrow Daffodil I would argue that any garden, ornamental, vegetable, or food forest, would benefit from plants that serve these functions. Your typical nursery may not have all of these plants; Natureworks does, or it can order them if they're not in stock when you visit. You can also try your hand at growing them from seed, as I am doing with many of them, but a potted plant will give you quicker and more guaranteed results. From early November to Early January I didn’t really do anything with the yard. Wasn’t even interested in it, really. My energy really tanked after moving the final bits of the wood chip pile on Halloween, and I just went inside. It was good to take a break from the project, until doubts crept in. As I huddled on the couch, my brain berated me: “this project is ugly and stupid and what do you know about growing a food forest anyway, and you can’t make a decision about anything”. Well, the whole point of this is that I don’t know that much about growing an integrated vegetable and tree garden. I’ve learned by reading books this year. Anyone can do that. This entire project is meant to prove that an ordinary person can grow food for themselves and for wildlife. It’s designed to inspire you to read the books yourself, or just plant some things and see what happens. So...enough from you, Doubt Brain. (Actually I think doubts are helpful as long as you don’t succumb to them; they make you justify your actions and it feels good to make decisive choices having faced your fears.) I arose from my indifference around the New Year, when my friends were over and asked about my project. I explained my planting plan to them, and showed them what I call my Paper Dolls, which I’ve been using to decide what goes where. They were very excited, and their encouragement got me excited again about my project. I finished my plan, and I want to share it with you. There are my paper dolls! Regular landscape designers create a base map with dark lines and draw shapes for plants on tracing paper over it. I would have used a million sheets of tracing paper; I have moved these darn things around so many times trying to figure out the best arrangement. Sometimes it felt like I was spending too much time on it, but I figure if I'm going to spend a long time on something, it might as well be the planning process. To create the base map, I measured my yard and drew a scale drawing on graph paper. I then cut to-scale squares of the trees and shrubs I was considering including. I colored them to make them beautiful and easy to identify. Oh, and fun to play with. Scale-size trees and shrubs are a low-risk way to see what might fit in your yard. I had a 100 foot Chestnut tree paper doll. Guess who got cut up into smaller trees when she took up the entire yard? I included limitations on my base map: -Septic leaching field in the backyard: no trees or shrubs can go on here, since their roots will potentially damage the system. Raised vegetable beds or a meadow could possibly go on here, but that's another task for another day. -Underground gas line in front: no shrubs within 6 feet, no trees within 25 feet. Once again, this is so that their roots don't damage the line. Paw Paw roots are less aggressive, so I chose to plant those nearest the line. Vegetable and meadow roots are delicate and would not damage the line. -It's not really a limitation, but I sought to include as many native plants as possible. They provide food and habitat for insects and birds. (Read more about this is Doug Tallamy's Bringing Nature Home). It's easy to get carried away with wanting different kinds of fruit trees, but reminding myself to include native plants helped create a final product that's really for everybody. The backyard came together first. Along the back slope will be berries. "Blub" means blueberry, "Elderb" means elderberry. Berries can be unruly, and can spread over the years, especially raspberries and blackberries, so I put them way in back. Currently there is a lilac bush where the elderberry will go, so replacing that is a long-term project. All of these berries are native. I wanted an elderberry a) because they make immune-boosting syrup b) because they feed wildlife and c) because in the Middle Ages, people planted elderberries at the head of their gardens to watch over everything, and I think that’s a lovely idea. Three tiny apple trees and an apricot tree are down the slope near the deck. These are not dwarf trees, which have weak root systems and are generally unhealthy, they are standard fruit trees that will be raring to reach 30 feet tall but I'm going to use a pruning technique to keep them 6 feet tall. None of these types of trees are native. When planning trees, you should plan how they will be watered. Admittedly, I don't have a tight scheme for this right now. These trees will hopefully be watered by a ditch dug next to the sidewalk to harvest the water running down from the rest of the street. I’m at the bottom of a slope, and an incredible amount of water runs by my house to the sewer, and I’m going to try and grab some of it to water my trees. If that doesn't work, I will run drip irrigation. The plum cluster is three trees planted so close together that their branches intermingle. This is the pollination technique recommended by Fedco Tree Catalog. (Pollinating plums is apparently notoriously difficult). I will have two American Plums that I will grow from seed, and one hybrid plum (Santa Rosa) which is bred for larger fruit size and better flavor. The two American Plums will also produce fruit, but it will be smaller, with a flavor determined by the genetic lottery. American plums are host to hundreds and hundreds of insect larvae, which in turn will be excellent food for baby birds. If I lose fruit because of that, fine. "No food" written by the house is a reminder that no food should be grown within three feet of old foundations, due to lead concerns. In the front yard, I have two Paw Paws and a persimmon. All native, all standard-size trees that I will prune to be 6 feet tall. Paw Paws need two individuals for pollination. Typical persimmons need three or more, but I will get a self-fertile one. A grapevine will climb the existing dogwood tree, and a 6-7 foot bush cherry and tiny-pruned peach tree will be in front of that. I drew a faint path just to give myself an idea of how I would move through the yard.

There are still a few unplanned spaces--the side of the house, the back yard in front of the shed. I'll leave those smothered in cardboard and leaves for now, since I've got my work cut out for me. This whole plan will be implemented in Spring and Fall 2020. This plan has come about through copious reading. The absolute best book I read was Creating a Forest Garden: Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops by Martin Crawford. I've heard that Edible Forest Gardens by Dave Jacke and Eric Toensmeier is very good too. I'll be getting the trees mostly from Fedco Trees mail order. Some will come from Cricket Hill Garden in Thomaston CT, and some will come from Cummins Nursery in upstate New York. All good sources to check for fruit trees. Click here to go to Part II: Understory Plants |

Categories

All

Archives

August 2021

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed